Inclusive economy? To restart social mobility, we must close the Participation Gap

By Tim Thorlby

5 mins

This blog is about how we can restart the stalled engine of social mobility and the crucial role that higher education plays in this. By looking at a case study of one English city – Sheffield – we can see the participation gap clearly and see what needs to change, and how. The prize is to shift historic patterns of deprivation once and for all.

This is the third blog in a short series looking at what ‘inclusive growth’ might look like and how to make it a reality.

1 - From the farm to the city

My grandparents were all farmers in the east midlands. Hard working small-scale farmers, nothing grand.

My parents were each the first generation in their respective families to live an urban life in a town and get a higher education. My mum went to university at a time when relatively few women did so (she was a determined lady) and my dad earned a qualification through “evening school” (as he called it).

My brothers and I all went to university; it seemed the normal and expected thing to do. We were encouraged to do so.

In just two generations, our family have moved from the countryside to the city and into a culture where higher education is a normal expectation and pattern.

How did it happen? I can’t tell you for sure as many of the stories are sadly lost in family history, and I never met most of my grandparents. But I do know that the transition to higher education and professional qualifications put our family onto a new and different trajectory entirely. It’s one small example of social mobility in action.

Once upon a time, this story would have been fairly common. Today, things are different.

2 - Searching for a new golden age

As I noted in the first blog in this series, the evidence shows that social mobility in the UK has stalled. The Sutton Trust’s most recent analysis suggested that a ‘golden age’ of mobility had now been replaced by one of declining opportunities. Patterns of disadvantage don’t seem to change from generation to generation. Today it is much less likely that children will have different trajectories to their parents.

In particular, education, once seen as the ‘great social leveller’, is no longer delivering these kinds of social impacts, despite many year-on-year improvements in the education system as a whole.

How is it possible that our education system as a whole is producing ever more qualified people yet social mobility is not happening?

It’s a big deal. There is plenty of evidence that those who have higher qualifications earn more as a result. There is a national business case too, as a recent report from Demos showed[1]; our economy as a whole would benefit from greater social mobility through enhanced productivity and innovation – making better use of our national talent pool.

So, what is going on? What must we do to restart the engines of social mobility in this country?

I thought that taking a case study of one English city might help us unravel some kind of answer to this question. Having recently arrived in the city of Sheffield, my newly adopted home, I have been getting to know the place and researching its challenges and opportunities. Along the way, I may have found at least part of the answer to this question. So, let’s briefly look at Sheffield as a microcosm of life in the UK.

3 - Sheffield: a tale of two cities

Sheffield, in South Yorkshire, is one of England’s larger cities, with over half a million residents. It just falls within the most 20% deprived local authorities in England overall, but it is, socially and economically speaking, a fairly typical city when compared to the UK’s other ‘Core Cities’ and in some few respects, it is above average – for example in its greenery and overall levels of health and life expectancy.

Although it still calls itself the ‘Steel City’, this kind of traditional industry accounts for few jobs these days and the overall level of manufacturing activity in the city is no greater than most other English cities. Indeed, one of the distinguishing features of Sheffield’s economy is the relatively lack of private sector jobs in comparison with its city peers and the below average level of business start-ups and productivity. It also has the unique distinction of being the only city in England which has a net out-migration of senior executives every day; the lack of head offices in the city means that senior managers love to live here, but they often don’t work here.

One of the other most striking features about Sheffield is the stark geographical segregation of wealth across the city.

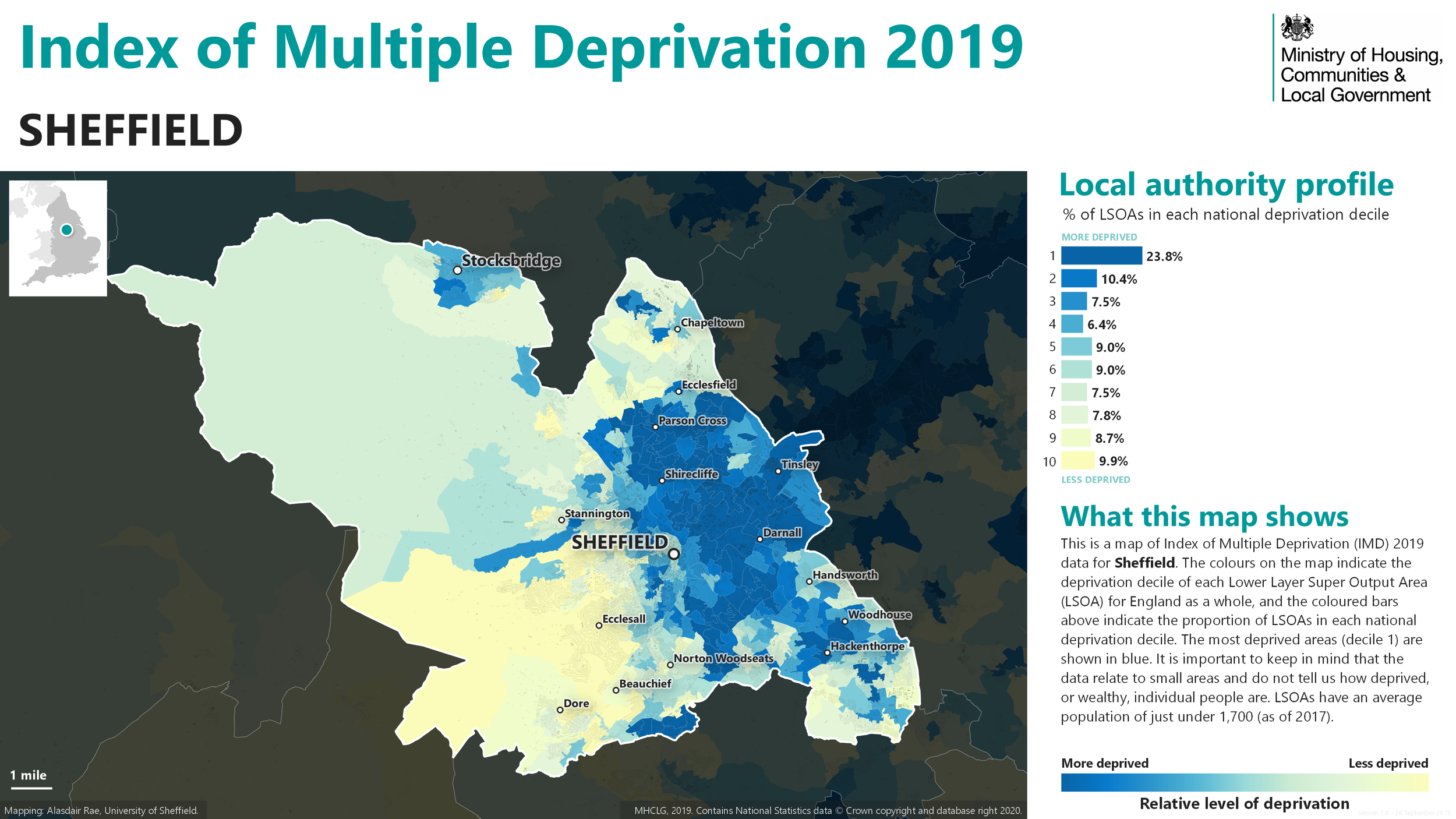

The map of multiple deprivation in Figure 1 clearly shows how the most deprived neighbourhoods in the city are distributed across the east and north (the blue areas) and the wealthier areas are found mostly in the west and south (the yellow areas). This level of segregation is striking, but also a fairly normal arrangement for an English city, so Sheffield is by no means unusual in this (in fact, what is unusual about Sheffield is the presence of substantial areas of wealth within the city boundary, but that is another story for another day).

Figure 1: Index of Multiple Deprivation 2019 data for the City of Sheffield

The 2012 Sheffield Fairness Commission[2] illustrated the city’s wealth disparities by showing how life expectancy fell by a decade along the route of the No. 83 bus as it travels from Ecclesall in the south west of the city to Burngreave in the north east. This has not changed in the last ten years.

Indeed, the pattern of deprivation in Sheffield has not changed in over 30 years.

So, what would it take to change it? How could the once-busy engines of social mobility be kick-started again here?

I think I found the answer buried in a pile of statistics.

Although east and west Sheffield represent ‘two cities’ in many respects, the statistical differences between them are not always huge; often shades of grey rather than a stark contrast. But I found one glaring exception to this; the rates at which young people in each neighbourhood of the city participate in Higher Education, or not.

This data on participation in higher education shows a yawning chasm in experience between the two sides of the city – and a key reason why social mobility has stalled here.

4 – The Participation Gap

In Sheffield, the proportion of 16 year old state school pupils who go on to participate in Higher Education by the age of 18 or 19 is fairly typical overall. But when you break it down by neighbourhood, the experience varies starkly across the city.

This ‘participation gap’ is shown on the map in Figure 2, with the darker colours showing where participation in higher education is higher[3].

Figure 2: Higher Education participation rates in Sheffield by area

Participation in higher education varies from just 19% in Southey (a large estate in north Sheffield) to 70% in Fulwood (a leafy suburb in south west Sheffield). In Southey, only two out of ten young people progress into higher education. In Fulwood, the rate of participation is nearly four times higher, at seven out of ten young people.

This difference is partly about how children fare at school and the varying GCSEs and A-Levels they emerge with, but these differences in attainment are not nearly enough to explain the breadth of the participation gap in higher education. There are also important social and cultural factors affecting why some families and communities access higher education more readily – this is partly about expectations, social networks and knowledge. Some families simply have more confidence, know-how, networks and encouragement to make this happen.

If we are to restart social mobility and bring our deprived communities in from the economic cold once and for all, then participation in higher education is at the heart of what needs to change and where we need to bring about systemic change.

I would like to clarify two things at this stage. Firstly, I would define ‘higher education’ to include good quality apprenticeships too. So, this agenda is not just about getting ever more young people to go to university. Vocational education needs a significant boost in this country because it is the best route for many of our young people and important for our economy. Secondly, and related to this, I am not advocating another expansion of universities, I think the sector is probably big enough already; I think a significant expansion of high quality vocational education (including apprenticeships) is required, so that our young people – wherever they grow up – have a proper choice of what kind of higher education they benefit from – whether academic or vocational or a hybrid. More young people from Southey should be going to university; and more young people from Fulwood would also probably be happier learning through high quality apprenticeships.

How big is the participation gap in Sheffield? I worked out for the City of Sheffield how many extra 18 year old students would be participating in higher education if the low participation areas were ‘levelled up’ to 50%. The answer is 2,500 students per year.

This is what it takes to restart social mobility in one of the larger cities in England – just another 2,500 students entering higher education across the whole city. It would transform the geography of opportunity in the city. Is that beyond us?

5 – A new golden age of opportunity?

The UK has made good strides in recent decades in getting more young people into higher education as universities have expanded, but it hasn’t made such a big difference to social mobility because we’ve been much better at getting middle class children into university than those from lower-income backgrounds. This is what needs to change. The good news is that we already know what we need to do; evidence abounds about ‘what works’ and the ’participation gap’ is now being well measured.

In brief and drawing from the available evidence, we need to:

Continue investing in early years and school education – clearly, continuing to improve educational attainment in all of our schools remains essential and there is still much work to do to close the attainment gaps in our towns and cities.

Require universities to widen participation – Universities themselves have many levers at their disposal to widen participation if they choose to do so. Modest progress has been made in recent years overall. Some universities are very good at it. Some have yet to bother much. The Higher Education Statistics Agency (HESA) helpfully collects performance data on this[4]. Liverpool Hope University tops the table with 32% of its students from ‘low participation neighbourhoods’. The University of Oxford sits almost at the bottom with 1.4% of its students from such areas. There is much scope for change here. Local action can make a big difference.

Expand apprenticeships – This is a huge challenge and requires public investment on a new scale, but the time has surely come to properly resource vocational education in the UK, from expanding FE to high quality industry-led apprenticeships. This requires a national solution but there are also choices which can be made by regional and sub-regional partnerships to prioritise investment in such institutions. There is scope for change here too, even in an age of tight finances.

Engage employers to help – A greatly underused resource and opportunity can be found in the nation’s employers – public and private. The best employers, as identified by the Social Mobility Employer Index[5], already work hard to engage with their local schools, reach out to students at university and operate recruitment practices that all contribute to widening the talent pool they have available. There is huge scope for movement here.

Charities and social enterprises – There are also a number of charities and social enterprises that work with particular groups and communities to increase HE participation rates. Organisations like The Brilliant Club (using PhD students as ambassadors), Brightside (online mentoring), The Access Project (tutoring and mentoring) and Into University (local learning) have a proven track record of success, they just need more funding! These plug the gap not being filled by the state and there is always scope to do more here too.

These sorts of changes, together, would link all of our neighbourhoods into the opportunities available through our economy. In the long run, ‘inclusive growth’ has to engage higher education in a full and substantial way.

The route to bridging the structural gap between rich and poor runs through the local secondary school and our local colleges and universities.

Only when the sons and daughters of the estates of Southey have the same opportunities as the children of Fulwood will we finally know what an inclusive economy looks like. And I have a feeling it will look pretty good.

This blog was written by Tim Thorlby. Please sign up for the email alert if you’d like to know about future blogs, usually published once a month.

Notes

[1] Huband-Thomson, B (2024) The Opportunity Effect: How social mobility can help drive business and the economy forward, Demos

[2] Sheffield Fairness Commission (2012) Making Sheffield Fairer

[3] The data and the map are drawn from Local Insight, provided by Sheffield City Council: https://sheffield.localinsight.org/#/map?savedmap=658

[4] Data freely available at: https://www.hesa.ac.uk/data-and-analysis/performance-indicators/widening-participation

[5] The Index is run by the Social Mobility Foundation; https://www.socialmobility.org.uk/employerindex