The Empty Chair: Britain’s missing workers

Photo by Ashima Pargal on Unsplash

By Tim Thorlby

7 mins

The UK has a million job vacancies and a shortage of workers. Yet millions of workers have been leaving the workplace in recent years. But why? Who are they? And will they ever return? This blog explores who Britain’s missing workers are.

1 – An incomplete story

In some respects, the current story about the UK’s economy looks quite good – high employment and low unemployment. Some politicians repeat this like a mantra as though it was all you need to know.

However, there are two crucial pieces of the story missing.

Firstly, there are nearly 1 million job vacancies today too[1]– which is a pretty high vacancy rate compared with recent years. It reveals a clear and unfulfilled demand for workers. This is one of the things holding the UK economy back at the moment – there are too many unfilled vacancies in too many workplaces, including public services. And this is for an economy stuttering along; imagine what would happen if the economy revived? So, far from having reached a ‘happy place’, the UK economy is unsustainably short of workers. This is also a key driver of high immigration rates at the moment, as employers look overseas to try to fill gaps.

Secondly, outside of ‘employment’ and ‘unemployment’ there is actually a third group of over 9 million adults who are of working age but not working. This is quite a lot of people who have, for various reasons, counted themselves out of the working world; neither employed nor unemployed. Off the pitch, to use a football metaphor. The lovely term given to them by the Office for National Statistics (ONS) is ‘economically inactive’.

It seems that many of these people are also not in a ‘happy place’ either:

There is a record number of people who have a long-term illness - nearly 3 million people.

There are also nearly 2 million people who would actually rather be working. Wouldn’t that help to fill some job vacancies? So, why aren’t they?

A wider view of our working age population suggests that there are millions of people outside of our working economy and not terribly happy about it. In this blog, I want to meet this group of people and understand a bit more about their situation.

2 – What is ‘economic inactivity’?

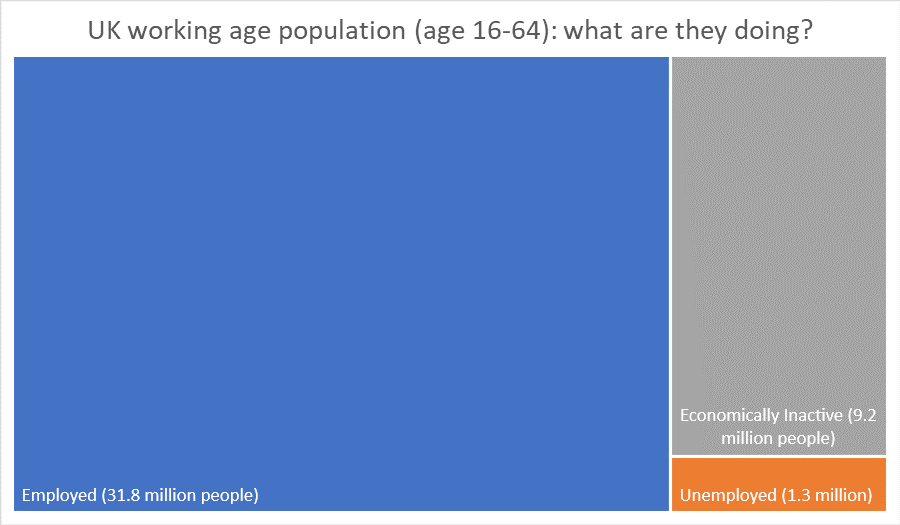

Firstly, a quick overview of what the UK’s ‘working age’ population is doing, using recent ONS data[2]. Take a look at the chart:

Our ‘working age’ population excludes children (under 16) and also most of our older and retired people (65 and over). It is all UK adults aged 16-64, which includes:

75% in employment

3.9% registered as unemployed

21.8% ‘economically inactive’

This last category is quite large, some one in five working age adults. It is at its highest level for nearly a decade and has risen noticeably since the pandemic. Who are they?

Understanding ‘Economic Inactivity’

The first thing to say is that people who are not active within the world of paid work are not necessarily ‘inactive’! These 9.2 million people are aged 16-64. They are not working for a variety of reasons. They include millions of students, many people looking after family at home and a few who have retired early. It also includes those who are long-term sick.

A look through the latest ONS economic inactivity data reveals three important strands of this story:[3]

Long-term sickness is historically high - The number of people who are long-term sick is at an historic high in the UK; higher than at any point in the 30 years that ONS have been collating these statistics. Some 2.8 million people are of working age but are out of work and long-term sick today, accounting for 30% of all economic inactivity – the biggest group. This is not normal.

Unemployment is more than double the official rate - One in five of the economically inactive – some 1.9 million people – would actually like to work but are not doing so. But they are not counted as “unemployed” because they do not claim any unemployment benefit and so do not appear in the unemployment statistics; the ‘claimant count’ is officially 1.3 million unemployed working age people today. Yet this additional 1.9 million people who are not working say they would like to. So the real number of people who are unemployed is more than double the official count.

Buried within the ONS data is also a peculiar statistic which I have never noticed before. The ONS counts ‘discouraged workers’; people who are out of work and have stopped looking as they believe there is no relevant work for them any more. This accounts for 29,000 people today. A rather sad statistic of despair.

Economic inactivity varies regionally – the rates vary significantly between regions, from 25.4% in the North East to 18.8% in the South East of England. This is a reminder that the ‘economic inactivity’ story varies around the country.

Let’s take a deeper look at these two large, overlapping, groups of ‘inactive’ people – the long-term sick and those who want to work but are not officially counted as unemployed.

3 – A deeper look: the long-term sick

The single biggest group amongst the ‘economically inactive’ of working age is those who suffer from ‘long-term sickness’. It has risen by one third since the pandemic to 2.8 million people, a record high for the last 30 years and the main cause of rising economic inactivity in the UK.

Whilst many other countries saw a similar rise in sickness during the pandemic, they subsequently saw their working populations return to normal afterwards - the UK is almost alone in seeing long-term sickness persist and continue to grow. Our national experience is not normal – not normal for us, nor in comparison with other European countries.

Who?

More than half of those who are long-term sick are in the oldest part of the working population, aged 50-64, and this group has increased the fastest since the pandemic. Yet every age group has seen a substantial rise in ill health, even the youngest.

Many of these people were previously working in lower-income occupations.

The biggest rises in long-term sickness have been in Wales, the SW of England, the North West and Yorkshire and the Humber.

Why?

What has driven the increase in long-term sickness? It appears to be a mix of factors.

The Covid pandemic itself has left hundreds of thousands of people with ‘long covid’ which can limit their ability to work. Estimates vary, but the OBR estimated in March 2023 that perhaps 1 million people of working age in the UK were still experiencing covid symptoms more than a year after falling ill[4].

This has coincided with, and partly driven, a substantial increase in the NHS’s waiting times; there is currently a queue of 7.8 million people for treatment, a record, meaning that many people are waiting a long time to be treated[5].

There is also growing evidence that over the last decade the underlying health of our population has stagnated overall and deteriorated in some respects. Improvements in life expectancy stalled for the first time since records began and many indicators of physical and mental health have also stalled or even decreased, even before the pandemic[6].

This toxic mix of a pandemic, an overwhelmed health service and a decade of public-sector austerity is what has driven the rise of long-term sickness, and in turn, the increase in economic inactivity.

What?

The majority of people who are long-term sick have multiple health conditions[7]. Long waits for treatment is clearly making the situation worse, as the number of people in each age group reporting multiple health conditions is rising over time. Over 60% of those who are long-term sick have been economically inactive for three years or more.

The most common primary health issue identified is ‘musculoskeletal’ which encompasses a wide range of back, neck and limb health issues, but there are often secondary health problems too.

Half of those who are long-term sick also suffer from depression or anxiety – it is rarely the primary health condition for this group, but unsurprisingly it becomes a common part of the challenge they face.

Economic cost?

In addition to the obvious human cost of ill-health there is also an economic cost – it doesn’t make much sense for our economy either.

The OBR have estimated that each person who becomes economically inactive due to ill health costs the government £26,600 per year in welfare payments, higher health service costs and foregone tax revenue. So, they estimated that the rise in long-term sickness since the pandemic alone may be costing the government £16 billion per year[8].

4 – A deeper look: the hidden unemployed

Let’s take a look at the second group of ‘economically inactive’ people.

Next to the 1.3 million people officially unemployed, looking for work and engaged with Job Centre Plus are another 1.9 million people who are unofficially unemployed, looking for work and unknown to our employment service. That means there are a total of 3.2 million people unemployed today and the majority - 60% - are not on any official list.

Who are they?

The vast majority of the ‘unofficially unemployed’ are people who were previously working and would like to work again, but have experienced some kind of disruption or hiatus; sometimes planned, often not.

They include people who have been made redundant or were dismissed as well as people in temporary jobs that came to an end. The group also includes people who were unwell but are now recovering, some early retirees who have changed their minds, as well as those who have taken time out to retrain or gain a qualification. There is also a group who cite a range of other personal, family and other miscellaneous reasons[9].

There is no stereotype and nothing in particular that they have in common other than that they are not working but are hoping to return to paid employment. One other thing they do share is that they have all chosen, for whatever reason, not to engage with their local Job Centre Plus. That more than half of our nation’s unemployed prefer not to engage with our national employment service should give pause for thought; it may say something about either the effectiveness of its outreach or perhaps its rather unsympathetic reputation. This is surely a problem that needs addressing.

Rather more concerningly, a fair number of the unofficial unemployed are young people aged 16-24. Nearly half a million young people, aged 16-24 are not in education, training or employment of any kind, nor are they registered as unemployed[10]. Half a million young people have left school and fallen off the radar.

If you add them to the half million young people who are registered as looking for work, then they form part a cohort of one million young people who are not in education, employment or training – the so-called NEETs. Although the number of NEETs is lower than it was in the aftermath of the Financial Crash in 2008-9, we don’t seem to have learnt much in the last 15 years. One million young people not getting on with their lives seems a colossal waste.

5 – Where did Steve go?

What is this blog about?

There are probably more statistics than a blog ought to contain (sorry) but that is my way of trying to show you something which is difficult to see any other way, because it’s hard to notice something that isn’t there.

Millions of people have disappeared from our workplaces (and schools and universities) all over the country in the last few years and are no longer visible to most of us. But I found them in our national statistics, lined up in the rows of a spreadsheet.

These are Britain’s missing workers – millions of them.

These dry statistics show us the millions of hidden unemployed who don’t go to the Job Centre, the half million young people who are ‘off the radar’ and thousands of ‘discouraged workers’ who have given up looking. They want to work, but they are not. The one thing this disparate group of people have in common is that they are not receiving any obvious support to get back into work or restart their lives. They have been forgotten.

Where did Steve go? You know, the guy who had the corner desk? Was he one of those laid off last year? Did anyone keep in touch?

The spreadsheets also show us the millions of people languishing at home with a variety of painful long-term illnesses and health conditions, waiting for something to happen. They are waiting for the letter from the hospital that says they have finally reached the top of the longest waiting list in the NHS’s history. Most of them used to go to work, but now they don’t, and many have been waiting for years; no wonder half of them are depressed. This group also defies stereotypes as it includes hundreds of thousands of young people – teenagers and twentysomethings. Some of them could be working today, but they are not.

Where did Lucy go? You remember, she used to come in for the morning shifts. Didn’t she hurt her back or something? Has anyone seen her recently? I hope she’s OK.

These are Britain’s missing – and forgotten – workers. Millions of them.

Hopefully they are not forgotten by those colleagues they used to work with, but they have been comprehensively let down by the society that is supposed to look out for them and support them.

To ignore these forgotten workers is an economic mistake. It is a huge waste of natural talent and resources, especially in a nation short of workers. It is also costing the nation money to keep them on waiting lists, paying out welfare benefits, foregoing tax revenues. As the OBR have helpfully pointed out, in the long run, getting people back to work grows our national economy. A healthy and engaged workforce underpins a healthy and vibrant economy.

To ignore these forgotten workers is also a social mistake. Part of our national social contract is that we look after each other; these mutual bonds are what makes for strong communities and a resilient society. It’s one of the things that makes us a civilised and decent nation. Many of these forgotten millions are formerly low paid ‘key workers’ who we banged saucepans for during the pandemic – national ‘heroes’ who went to work while we stayed at home; the nurses, the social carers, the cleaners, the delivery drivers. We owe them something.

Some in the UK have a mindset about public services that sees them purely as a cost which must be driven down. This is a misunderstanding. To support the health and flourishing of our families and neighbours is an investment in the future of our social fabric and in the growth of our economy. And given that, even today, the UK remains one of the wealthiest nations on earth, the idea that ‘we can’t afford it’ is hard to credit. The austerity mindset has completely failed this country and it has failed on both social and economic terms; it has achieved nothing of value.

I usually offer a brief theological reflection in these blogs, but sometimes the point seems so obvious I’m not sure I need to bother. It seems self-evident to me that we must be prepared to invest in support for those workers who have been forgotten – health care and employment support. Why would we not? As Mark Twain once remarked:

“It ain't the parts of the Bible that I can't understand that bother me, it's the parts that I do understand.”

The challenge is not unpicking some complex understanding, but rather finding the will to do something about the obvious problem in front of us.

6 – Let’s go to work

A healthy workforce is essential for a healthy economy. We need to reimagine our health service as an investment in a healthy and flourishing society, out of which our economy operates. It may cost more money. It may actually pay for itself. Restoring the NHS to once again be a world-class health service seems a good ambition for the next decade.

With respect to those millions who are out of work but never step through the doors of their local Job Centre, the answer may be more complex. I personally think there are serious questions to ask about the effectiveness of our national employment service and its ability to reach, engage and support people. With nearly 50 different government schemes managed by multiple Whitehall departments, and limited local discretion, there is little wonder it doesn’t work.

I think the answer is to fully devolve our employment service to the local level and our local authorities, employers and colleges to work together in each area - with outreach and support services fully devolved and locally led. Local organisations are more likely to reach and engage people and be able to join up training provision and employment support and links to local employer. Local partnerships could work with local business, social enterprises, local FE/HE institutions, the voluntary sector and local communities. In other words, it requires a complete rethink about how we help people into work in the UK, with an emphasis on locally-led partnerships to get people back into work. There are many pilots and initiatives and models to learn from.

Where did Steve and Lucy go? Can we help them?

This blog was written by Tim Thorlby. You can sign up here for future blogs if you’d like to know when they are published.

Notes

[1] 932,000 job vacancies recorded by ONS, February 2024

[2] All of this data is for the UK, Oct – Dec 2023. For further information see: Office for National Statistics (ONS), released 13 February 2024, ONS website, statistical bulletin, Labour market overview, UK: February 2024

[3] Data is for the UK, Oct – Dec 2023. See: Office for National Statistics, released 13 February 2024, ONS website, INAC01 SA: Economic inactivity by reason (seasonally adjusted)

[4] Drawn from: OBR (2023) Fiscal Risks and Sustainability Report, July 2023: https://obr.uk/frs/fiscal-risks-and-sustainability-july-2023/#chapter-2

[5] For the latest NHS statistics on waiting times: https://commonslibrary.parliament.uk/research-briefings/cbp-7281/

[6] For some discussion of life expectancy trajectories in the UK, see: https://www.ons.gov.uk/peoplepopulationandcommunity/birthsdeathsandmarriages/lifeexpectancies/bulletins/nationallifetablesunitedkingdom/2018to2020

[7] For a recent 2023 analysis, see: https://www.ons.gov.uk/employmentandlabourmarket/peoplenotinwork/economicinactivity/articles/risingillhealthandeconomicinactivitybecauseoflongtermsicknessuk/2019to2023

[8] OBR (2023) Fiscal Risks and Sustainability Report, July 2023 | Available here: https://obr.uk/frs/fiscal-risks-and-sustainability-july-2023/#chapter-2

[9] An excellent analysis of this group can be found here: Evans, S., Clayton, N. and Vaid, L. (2023) Missing workers: Understanding trends in economic inactivity, Learning and Work Institute

[10] For data on NEETs see: https://www.ons.gov.uk/employmentandlabourmarket/peoplenotinwork/unemployment/bulletins/youngpeoplenotineducationemploymentortrainingneet/august2023